|

| Good ol' Nicky Gerber. |

From there it was a relatively (and, at times, absolutely) straight shot up I-41 to the Upper Peninsula. Never had I seen an interstate highway so hypnotically flat and level--certainly none with four lanes of traffic on each side. Without curves or hills or any meaningful change in scenery, there was nothing to hold my attention to the road--even at 80 mph it felt like I was barely moving. I had to sing to keep my mind from straying. Up I shot through Oshkosh, Appleton, Green Bay...

...and then, more or less at once, the Midwestern cornfields turned to forests and the interstate to rural, two-lane US-41. The traffic disappeared, leaving me alone on the road. This region, the Great North Woods of the Upper Midwest, was without a doubt the remotest, sparsest places I’d yet driven through. There was nothing but trees, trees, and more trees for miles--pine, spruce, and birch, like in Maine--broken only by the occasional glacial pond.

A couple of hours later, I crossed the Menominee River into Michigan's Upper Peninsula (and back, temporarily, into Eastern time). Waiting for me was Iron Mountain, MI, a tourist town much like North Conway, NH, only without the obvious attraction of the White Mountains. The red-soiled hills around the town are as mountainous as the Midwest gets, I suppose. And even the flatlands have a certain quiet, wild appeal to them--plus it’s cold enough here that it’s actually nice to be outside in August.

|

| A quick stop beside the road. |

Despite these incidents, I arrived around 6 pm in L'Anse, MI, a small town along the Keweenaw Bay of Lake Superior with a legacy of fur trading and supplying wooden side-panels to Ford. The sun was still high in the sky, reflecting off the uncharacteristically calm waters of the bay.

|

| The rest of the Lake isn't quite so friendly. |

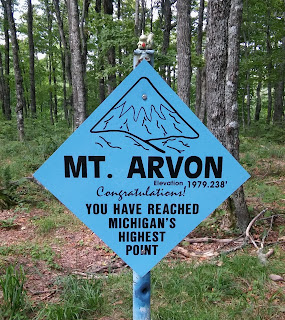

So, despite the lateness of the hour, I drove on down the northeast road towards Mt. Arvon. Along this road were scattered houses, gravel side roads, and unironically-named (I can only assume after seeing them all over the West) trading posts, but no sign of road I sought. I turned back after half an hour, thinking I must have missed the turn, but another half-hour's drive found me back in L'Anse none the wiser. Where was this place? I pulled into the campground and hopped back on their wifi... and it was a few miles past where I'd turned back.

The dilemma recurred: push on or stay here? I looked from my wallet to the bathhouse, from the tent sites to the setting sun:

|

| Photographed later. |

And so I bought a site, whipped up some supper, and settled in for the night:

-

I woke the next morning on Central-sunlight time (take that, Michigan state officials), availed myself of the plumbing, and three-traced that old road to Arvon.

The mountain went similarly to several high points I'd done before. Like Mt. Mitchell, I'd driven out, turned back prematurely, and had to turn around again to find the place (down a wide, well-graded gravel road named for the nearby Roland Lake). Like Mt. Sassafras, I drove partway up (on another, much rougher gravel road, past a lake and a naturally-occurring gravel pit which drew the Lars like a kid to an ice-cream truck--not before we exercise, I told them), then bailed when it grew steeper than my little Honda could handle. And like Mt. Marcy, the (remaining) approach was a long slog through the middle of nowhere.

|

| Beautiful, but sloggy nonetheless. |

|

| Nice try, Michigan, but your high point's still below treeline. |

but some large, clawed footprints I spotted in the dirt suggested I wouldn't like this place quite as much come nightfall.

But it turned out that I had nothing to fear save my own stupidity: I'd left my water bottle back in my car, thinking it was only a mile or so to the summit. Why would I need that big heavy thing on a long walk up a dusty road at midmorning?

|

| Why indeed? |

would have been so much prettier if only I'd been properly hydrated. But hey, that's life.

A half-mile later, the road wound up a false summit, then ducked away and continued on below the ridge; another half-mile, and I was there:

The only one there, it appeared, and the first to sign the summit log that day. I flipped through the other entries--some terse and factual, some reflective, and some marveling that their two-wheel-drive had made it up--then rested for a while in the grove, watching the breeze stir the treetops:

|

| Not realizing, of course, how I'd come to miss that sight in the arid West. |

|

| Tastes better after you've earned it. |

No comments:

Post a Comment